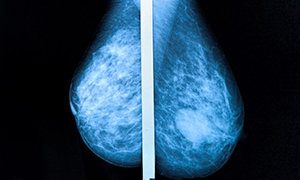

Guidelines for breast cancer management in Bosnia and Herzegovina

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2022.7504Keywords:

Breast cancer, Bosnia and Hercegovina, treatment, guidelines, consortium, breast, multi-disciplinaryAbstract

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, accurate data on the status of breast cancer are lacking due to the absence of a central registry. Multiple international guidelines imply that institutions that monitor breast cancer patients should have optimal therapeutic options for treatment. In addition, there have been several international consensus guidelines written on the management of breast cancer. Application of consensus guidelines has previously been demonstrated to have a positive influence on breast cancer care. The importance of specialty breast centers has previously been reported. As part of the 2021 Bosnian-Herzegovinian American Academy of Arts and Sciences (BHAAAS) conference in Mostar, a round table of multidisciplinary specialists from Bosnia and Herzegovina and the diaspora was held. All were either members of BHAAAS or regularly participate in collaborative projects. The focus of the consortium was to write the first multidisciplinary guidelines for the general management of breast cancer in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Guidelines were developed for each area of breast cancer treatment and management. These guidelines will serve as a resource for practitioners managing breast cancer in the Bosnia and Herzegovina region. This might also be of benefit to the ministry of health and any future investors interested in developing breast cancer care policies in this region of the world.

Citations

Downloads

Downloads

Additional Files

Published

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Lejla Hadžikadić-Gušić, Timur Cerić, Inga Marijanović, Ermina Iljazović, Dijana Koprić, Anela Zorlak, Mahira Tanović, Alma Mekić-Abazović, Ibrahim Šišić, Una Delić, Jasminka Mustedanagić-Mujanović, Alija Aginčić, Edin Bećiragić, Frederick Greene

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How to Cite

Accepted 2022-07-12

Published 2023-01-06